Mother of Army officer returns to United States and family following deportation

- Share via

Even after being deported from the United States and separated from her children and grandchildren, Rocio Rebollar Gomez never stopped believing in miracles — or praying for one of her own.

This week, her prayers were finally answered.

Rebollar Gomez was allowed to return to San Diego on Thursday about a year and a half after being forced to leave. Her case drew international attention in 2019 as her family pleaded with the U.S. government to give her permission to stay through a program for parents of active military members.

Her son, 1st Lt. Gibram Cruz, is an Army intelligence officer. He flew home from Ft. Hood to welcome his mother back into the United States. Because of his status in the military, he had not been allowed to cross the border to visit her after she was deported.

Cruz stood with his sisters waiting for more than five hours outside the San Ysidro Port of Entry for Rebollar Gomez to appear.

But in an unexpected turn of events, Rebollar Gomez was not allowed out to meet her family. Customs and Border Protection officials insisted she get on a bus with other families who had been processed into the country to go to a hotel in San Diego that has served as a migrant shelter for Jewish Family Service during the pandemic.

Her family scrambled to find her and reunite with her.

Rebollar Gomez’s crossing was made possible by the efforts of immigration attorney Dulce Garcia, who spent the last two months in Tijuana working with asylum seekers.

His mother, Rocio Rebollar Gomez, is praying for a miracle before her scheduled deportation date of January 2.

Garcia initially met Rebollar Gomez shortly before her deportation and amplified her family’s pleas to the public. After Rebollar Gomez was whisked away across the border while her family and attorney were still meeting with immigration officials to try to negotiate, her story stuck with Garcia.

“When Trump said anyone is deportable, no one is safe in the United States, I was hoping Rocio’s case would be the exception,” Garcia said. “Instead, we saw her taken away and deported even though the eyes of the world were on her and thousands of people had shown support for her. If she was being deported, any of us could be deported.”

Rebollar Gomez has no criminal history. She came to the United States without documents in 1988 and has been removed from the country several times, initially because of a raid on the hotel where she worked in the 1990s. Each time she was sent back to Mexico, she sneaked back in to be with her children.

During the Trump administration, she applied for a program that protects the parents of active military members but was denied. Immigration officials told her that she would have to leave, and on Jan. 2, 2020, she found herself sitting in El Chaparral plaza in Tijuana, calling her family to let them know that she had already been deported.

Her time in Tijuana was made worse by the pandemic. Her son was already not allowed to cross, and with the border closures, her daughters couldn’t cross either. Her mother died in the United States last year as well, with Rebollar Gomez unable to be by her side.

After Garcia traveled to Tijuana in March of this year, she invited Rebollar Gomez to lunch. During their conversation, Rebollar Gomez opened up to Garcia, telling her what she had not told her own family because she didn’t want them to worry — that she’d been targeted and attacked while in Mexico and was afraid for her life.

Garcia quickly got to work, adding Rebollar Gomez to the pile of applications she was working on for a new entry process created by negotiations in a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union.

That lawsuit challenged the legality of Title 42, a policy put in place by the Trump administration during the pandemic and continued under President Biden that allows border officials to immediately expel asylum seekers and other migrants without screening them for protection needs. Because of the court case, the federal government has agreed to allow the ACLU to submit requests for exemption from the rule.

The government then reviews those requests, and those approved are given a date to come to a port of entry to be allowed into the United States.

When Garcia received a message that Rebollar Gomez’s request had been approved, she leaped off her hotel bed in excitement. Then she asked Rebollar Gomez to meet her on Mother’s Day to reshoot a video interview that Garcia filmed as part of a documentary she was working on about her trip.

Filming at Playas, the beach in Tijuana where the United States border barrier reaches into the ocean, Garcia asked Rebollar Gomez what she would do first after going back to the United States.

Rebollar Gomez answered that she would go to church. Then Garcia told her that she had a Mother’s Day gift for her — revealing that she would, in fact, be going back.

Together they video-called Rebollar Gomez’s family to celebrate. Her youngest daughter couldn’t stop crying.

Since then, Rebollar Gomez counted down the days until she would leave Tijuana.

“At first I wasn’t sleeping because of the situation,” Rebollar Gomez said, referring to the insomnia she has experienced from the stress of her deportation. “Now, I’m not sleeping because of excitement.”

By Monday of this week, she had already packed her suitcase. As Thursday drew closer, she began to feel nervous.

She wouldn’t feel safe until she had actually crossed.

“It feels like a nightmare, and I still haven’t woken up,” she said. “Once I’m in San Diego, I’ll be able to breathe.”

But as journalists interviewed her throughout the day before her appointment with U.S. officials, she repeated a refrain that has led her through all of the difficulties — she was trusting in her faith.

“God sent me an angel in Dulce Garcia,” Rebollar Gomez said.

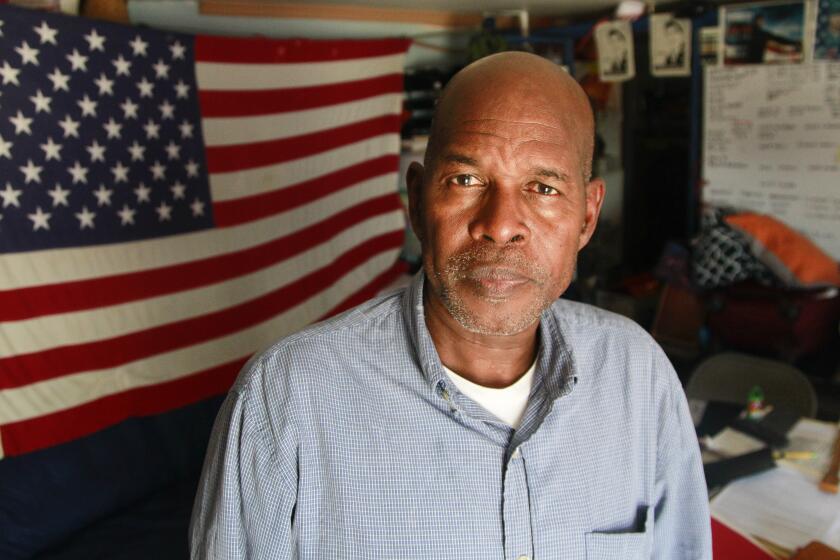

Roman Sabal, a U.S. Marine veteran originally from Belize, is now living in Los Angeles after more than a decade stuck outside the United States.

For Garcia, Rebollar Gomez has been an inspiration.

“Her faith is contagious,” Garcia said.

It is not yet clear whether Rebollar Gomez will ultimately be allowed to stay, but getting permission to be in the United States is generally easier from inside the country.

She will have an immigration court case to fight, and only time will tell how that resolves.

For her children, the stress of not knowing the ultimate outcome feels familiar.

“It’s like deja vu,” Cruz said, his voice filled with worry.

In the meantime, Rebollar Gomez plans to make up for lost time. Before her deportation, she worked 16-hour days to pay for her house and take care of her family. She’s looking forward to returning to that.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.